The purpose of this feature is to give scout leaders, educators and naturalists an idea of some of the natural events coming up each month. We will try to cover a variety of natural events ranging from sky events to calling periods of amphibians, bird and mammal watching tips, prominent wildflowers and anything else that comes to mind. We will also note prominent constellations appearing over the eastern horizon at mid-evening each month for our area for those who would like to learn the constellations. If you have suggestions for other types of natural information you would like to see added to this calendar, let us know! Though we link book references to nationwide sources, we encourage you to support your local book store whenever possible.

Notes and Images From October 2023 The first week in October found me in Nashville, making my way up a steep wooded slope towards a group of White Pines. I was looking for Bitter Oyster mushrooms. When I was learning about bioluminescence for last month's Natural Calendar I came across accounts of bioluminescence in Bitter Oyster mushrooms. Since it was said to be common in eastern North America, it seemed like a good species to check out. Bitter Oyster mushrooms are small and grow in clusters on decaying wood. At first glimpse they might be mistaken for one of the many white shelf fungi seen on downed wood, but they are gilled mushrooms rather than polypores. They have short stalks that intersect the caps at the periphery of the cap. The caps and stalk are beige, tinged with yellow or orange. They are found on both deciduous and coniferous tree species. When looking for them, think small - the caps of the mushrooms in the images below are mostly less than a half inch in diameter. My plan was to check the conifers first, then loop back downhill through a cove of hardwoods. Below just the second White Pine I checked I spotted a small cluster of mushrooms. The cluster was on a downed limb of the pine and the whole cluster was only about an inch and a half in width. The mushrooms ticked all the right boxes on identification, and a double check with the iNaturalist Seek app on my phone confirmed it; Panellus stipticus, Bitter Oyster mushroom, or as Seek called it, Luminescent Panellus. Talk about beginner's luck! This group unfortunately appeared rather desiccated and past its prime. The shriveled caps were hard to the touch. I was still happy because now we had a location that we could come back to and check over time. The fruiting bodies were said to appear in fall, winter and spring, and were said to be persistent. A cold front came through that night and brought some rain. We climbed the hill the next day and were amazed to find that the dried out mushrooms had reconfigured themselves in the rain and, in a little over 24 hours, were rejuvenated! The before and after images are shown below.

That night, almost as an afterthought, we decided to check on the mushrooms and trekked up the now wet and slippery slope to the White Pines. The second we turned off our headlamps we immediately saw the glow of the Bitter Oyster mushrooms! Although we couldn't see much detail with the naked eye, they were much brighter than the Jack-O-Lantern mushrooms we photographed last month. I immediately went back to the house and grabbed my camera and macro lens, and a piece of a cheap tripod that I had laying around. The tripod I normally used would have placed my point of view too high off the ground. Based on my experience last month, I used the same settings as I use photographing the Milky Way in pristine western skies - 30 seconds at a high ISO setting. When the image popped up on the back of the camera, we almost fell over! It was actually too bright! I had to stop down the aperture from f2.8 to f5.6. I made numerous exposures from the tripod at a couple of focus positions. The result is below.

Besides the mushrooms themselves, you can see the wet wood in the background glowing due to the mycelium embedded in it. No darkening of the background of the image was necessary - It was a dark moonless night and the only light visible in the image is due to bioluminescence.

The chemical reaction involves a substrate called luciferin, being acted upon by the enzyme luciferace in the presence of oxygen and ATP. Both the substrate and enzyme name come from the word lucifer (light-bearer), which was also used by the ancients as the name for the "morning star", or Venus as seen in the morning sky. Venus in the morning sky rises shortly before the Sun, hence the name. There are a number of chemically different types of luciferin. The luciferin in Panellus stipticus is 3-hydroxy hispidin. There are different suggestions as to the etymology of the word foxfire. Though some sources suggest that it may come from the French "faux" (false), others point to the circa 15th century word "foxwood", used for downed wood in the forest. The purpose of bioluminescence in mushrooms may be to attract insects that may aid in the dispersal of their spores. Though it is typically faint, there is at least one account of it being bright enough to read by. We learned a few things from our experience with Bitter Oyster mushrooms. First, it helps if you can locate a group of these mushrooms in the daytime. When coming back to them at night, a dark moonless night helps both with viewing visually and with imaging. If possible, go the day after a rain. For the best views visually, let your eyes have a chance to become completely dark-adapted. Use averted vision (looking to one side of the subject rather than directly at it) if necessary. Get as close to the mushrooms as you can; a faint object is more visible if it is spread across a large part of the retina of your eye. You can cup your hands around the mushrooms and place your face against your hands to shield out any ambient light if required. For photography, take a small tripod to allow you to get close to ground level. Take many photos at several focus positions. Start with an exposure of about 30 seconds (ideally use a remote release or a delayed release to minimize vibration). Adjust the ISO of the camera to produce the desired result. You can average several exposures to reduce noise in the image. Again, to isolate the luminescence from any ambient light it must be quite dark. As a rule of thumb, if you can see your surroundings with the lights off, there may be too much ambient light for photography. The best conditions are low light pollution, no streetlights, no moonlight, and a time past astronomical twilight, which occurs when the Sun is 18 degrees below the horizon. Apps like Sky Safari will tell you the local time of astronomical twilight. If you don't have an app, waiting two and a half hours after sunset will suffice for mid-temperate latitudes. The widespread occurrence of bioluminescence across different kingdoms in the natural world suggests that it goes far back in time. One hypothesis that has been proposed is that bioluminescence originally developed as one way for anaerobic life to adapt to increased oxygen produced by the "great oxygenation event" approximately 2.4 billion years ago.

Sky Events for November 2023: The Leonid Meteor Shower peaks during the morning hours of November 18th. A couple of lounge chairs, a blanket or sleeping bag, and a hot beverage will probably add to your enjoyment. Just face east and enjoy the night. Though this is not presently the most active meteor shower, you should still see a few meteors. Evening Sky:

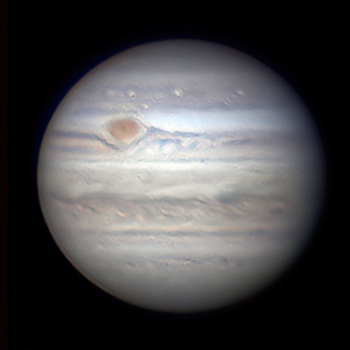

Look for Jupiter low above the eastern horizon at dusk this month. For good telescopic views wait till it gets 30 to 40 degrees above the horizon. There's a lot to see on Jupiter. Even with just a good pair of binoculars you can see Jupiter appears as a small disk rather than a starlike point. You can often see one or more of the four Galilean moons. One of Galileo's great discoveries were these four moons, though the names presently used (Io, Europa, Calisto and Ganymede) were suggested by his archrival Simon Marius. The movement of the moons is noticable even over the course of one evening. A six-inch aperture telescope will show the Great Red Spot, a long-lasting, Earth-sized storm in Jupiter's clouds shown in the image at right, and some of the belts, though the belts have lower contrast visually than they appear in images. The planet rotates in just under 10 hours, so in a single night you can watch the Great Red Spot rotate from one side of the planet to the other.

Saturn is about 35 degrees above the southeast horizon at dusk this month. The view is spectacular in just about any aperture telescope. The discovery of Jupiter's moons was a triumph for Galileo. Saturn brought him only frustration. His telescope was just not sharp enough to make it out clearly, and when the rings were at the angle shown in the image at right, the low-resolution image looked like one large disk with a smaller disk on either side of it (see the inset at right). Due to to the changing perspective that we view the rings, they appear to open and close to us. When he viewed Saturn a few years later the rings appeared edge on, and his two smaller disks had disappeared. He wrote in a letter, "What can be said about so strange a metamorphosis? Are perhaps the two smaller stars consumed, like the spots on the Sun? Have they suddenly vanished and fled? Or has Saturn devoured his own children?...I cannot resolve what to say in a chance so strange, so new, and so unexpected; the shortness of time, the unexampled occurrence, the weakness of my intellect and the terror of being mistaken, have greatly confounded me." The true nature of Saturn's rings was not discovered until almost 50 years later, by Christiaan Huygens, using much better optics. Huygens also discovered Saturn's largest moon Titan. Morning Sky: Venus still shines brightly in the eastern predawn sky this month. It is brighter than any other star-like object in the sky, so you shouldn't have a problem locating it. Mercury may be visible the last few days of the month low in the west after sunset. Look for it very low in the southwest 20 to 30 minutes after sunset. A flat horizon and binoculars will help, though take care not point them at the Sun. You can severely damage your eyes without knowing it.

Constellations:

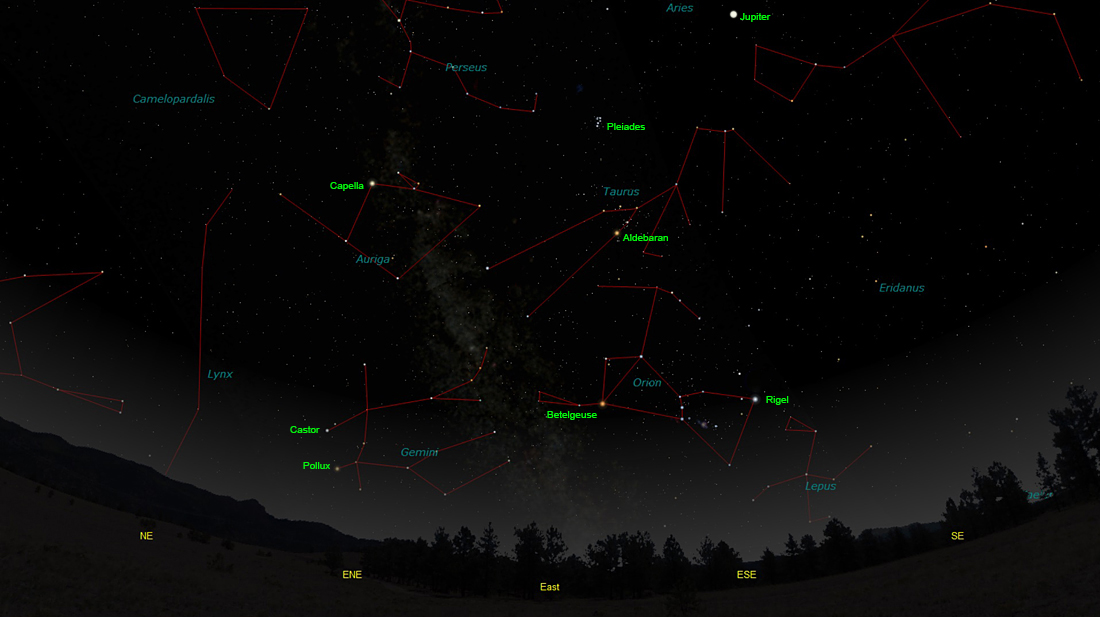

Auriga, the Charioteer, with its bright star Capella, is prominent in the northeast. Look for the bright stars Castor and Pollux as the constellation Gemini, The Twins, clears the horizon. In the southeast, mighty Orion clears the horizon with its bright stars Betelgeuse and Rigel. Note the difference in color between the two stars. Betelgeuse is a red giant and looks orange. Rigel is a very hot supergiant and looks bluish. Looking at the center of the three "sword" stars with binoculars, you can see M42, the Orion Nebula. Just poking its head above the horizon is Lepus, The Hare. Look above the bright star Aldebaran in Taurus to spot the Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters. Above the southeast horizon the stars of Eridanus, the River. The river begins near Rigel, at the foot of Orion, and winds its way down to the horizon and disappears below it. It ends in the bright star Achernar, which never rises above our southern horizon. Along its path lies the beautiful barred spiral galaxy NGC 1300, shown in the image above. This galaxy is almost 70 million light-years away.

On Learning the

Constellations: We advise learning a few constellations each month, and then following them through the seasons. Once you associate a particular constellation coming over the eastern horizon at a certain time of year, you may start thinking about it like an old friend, looking forward to its arrival each season. The stars in the evening scene above, for instance, will always be in the same place relative to the horizon at the same time and date each November. Of course, the planets do move slowly through the constellations, but with practice you will learn to identify them from their appearance. In particular, learn the brightest stars for they will guide you to the fainter stars. Once you can locate the more prominent constellations, you can "branch out" to other constellations around them. It may take you a little while to get a sense of scale, to translate what you see on the computer screen or what you see on the page of a book to what you see in the sky. Look for patterns, like the stars that make up Orion. The Earth's rotation causes the constellations to appear to move across the sky just as the Sun and the Moon appear to do. If you go outside earlier than the time shown on the charts, the constellations will be closer to the eastern horizon. If you observe later, they will have climbed higher. As each season progresses, the Earth's motion around the Sun causes the constellations to appear a little farther towards the west each night for any given time of night. The westward motion of the constellations is equivalent to two hours per month. Recommended: Sky & Telescope's Pocket Star Atlas is beautiful, compact star atlas. A good book to learn the constellations is Patterns in the Sky, by Hewitt-White. For sky watching tips, an inexpensive good guide is Secrets of Stargazing, by Becky Ramotowski.

A good general reference book on astronomy is the Peterson

Field Guide,

A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets, by Pasachoff. The book retails for around $14.00.

The Virtual Moon Atlas is a terrific way to learn the surface features of the Moon. And it's free software. You can download the Virtual Moon Atlas here. Apps: The Sky Safari 6 basic version is free and a great aid for the beginning stargazer. I really love the Sky Safari 6 Pro. Both are available for iOS and Android operating systems. There are three versions. The Pro is simply the best astronomy app I've ever seen. The description of the Pro version reads, "includes over 100 million stars, 3 million galaxies down to 18th magnitude, and 750,000 solar system objects; including every comet and asteroid ever discovered." You may also want to try the very beautiful app Sky Guide. Though not as data intensive as Sky Safari, Sky Guide goes all out to show the sheer beauty of the night sky. Great for locating the planets. A nother great app is the Photographer's Ephemeris. Great for finding sunrise, moonrise, sunset and moonset times and the precise place on the horizon that the event will occur. Invaluable not only for planning photographs, but also nice to plan an outing to watch the full moon rise. Available for both androids and iOS operating systems.

Amphibians:

Recommended: The Frogs and Toads of North America, Lang Elliott, Houghton Mifflin Co.

Archives (Remember to use the back button on your browser, NOT the back button on the web page!) Natural Calendar September 2023 Natural Calendar February 2023 Natural Calendar September 2022 Natural Calendar February 2022 Natural Calendar December 2021 Natural Calendar November 2021 Natural Calendar September 2021 Natural Calendar February 2021 Natural Calendar December 2020 Natural Calendar November 2020 Natural Calendar September 2020 Natural Calendar February 2020 Natural Calendar December 2019 Natural Calendar November 2019 Natural Calendar September 2019 Natural Calendar February 2019 Natural Calendar December 2018

Natural Calendar September 2018 Natural Calendar February 2018 Natural Calendar December 2017 Natural Calendar November 2017 Natural Calendar October 2017Natural Calendar September 2017 Natural Calendar February 2017 Natural Calendar December 2016 Natural Calendar November 2016 Natural Calendar September 2016Natural Calendar February 2016 Natural Calendar December 2015 Natural Calendar November 2015 Natural Calendar September 2015 Natural Calendar November 2014 Natural Calendar September 2014 Natural Calendar September 2013 Natural Calendar December 2012 Natural Calendar November 2012 Natural Calendar September 2012 Natural Calendar February 2012 Natural Calendar December 2011 Natural Calendar November 2011 Natural Calendar September 2011 Natural Calendar December 2010 Natural Calendar November 2010 Natural Calendar September 2010 Natural Calendar February 2010 Natural Calendar December 2009 Natural Calendar November 2009 Natural Calendar September 2009 Natural Calendar February 2009 Natural Calendar December 2008 Natural Calendar November 2008 Natural Calendar September 2008 Natural Calendar February 2008 Natural Calendar December 2007 Natural Calendar November 2007 Natural Calendar September 2007 Natural Calendar February 2007 Natural Calendar December 2006 Natural Calendar November 2006 Natural Calendar September 2006 Natural Calendar February 2006

Natural Calendar December 2005

Natural Calendar November 2005

Natural Calendar September 2005

Natural Calendar February 2005

Natural Calendar December 2004

Natural Calendar November 2004

Natural Calendar September 2004

Natural Calendar February 2004

Natural Calendar December 2003

Natural Calendar November 2003 Natural Calendar February 2003 Natural Calendar December 2002 Natural Calendar November 2002 Nature Notes Archives: Nature Notes was a page we published in 2001 and 2002 containing our observations about everything from the northern lights display of November 2001 to frog and salamander egg masses. Night scenes prepared with The Sky Professional from Software Bisque All images and recordings © 2023 Leaps

|

|