The purpose of this feature is to give scout leaders, educators and naturalists an idea of some of the natural events coming up each month. We will try to cover a variety of natural events ranging from sky events to calling periods of amphibians, bird and mammal watching tips, prominent wildflowers and anything else that comes to mind. We will also note prominent constellations appearing over the eastern horizon at mid-evening each month for our area for those who would like to learn the constellations. If you have suggestions for other types of natural information you would like to see added to this calendar, let us know! Though we link book references to nationwide sources, we encourage you to support your local bookstore whenever possible.

Notes From June 2023 In June we had a couple of enjoyable nights going on backyard insect safaris. I have a relatively new macro lens from Laowa that allows zooming in to two times life-size on the camera sensor, and this often results in some very interesting surprises. You often focus without being able to fully see the details in the viewfinder. This month we concentrated on Harvestmen, often called daddy longlegs or granddaddy longlegs, and Green Lacewings.

An urban legend about Harvestmen claims they are the most venomous spider on earth, but their mouth is too small to break the skin of a human. They actually have no venom glands at all. They use the small pinchers on the tips of their chelicerae to subdue and break apart prey. Unlike spiders, they do not have silk glands and they do not spin webs. The order name Opiliones comes from the Latin "opilio" (shepherd) and may refer to an ancient practice of shepherds standing on stilts to better see their herds. There are various suggestions on the origin of the common name. Some sources suggest the name comes from their common occurance during the time of harvest. Robert Hooke, 17th century scientist and natural philosopher, wrote in his 17th century book Micrographia of a superstition in Essex County, England suggesting that killing a Harvestman would result in a bad harvest for the year.Unlike spiders, Harvestmen do not use hydraulics to move their long legs. The second pair of legs is the longest, measuring over 3 inches long in the individuals that I photographed. This second pair of legs is also used to sense their environment. Harvestmen are very agile and move quickly on their long legs. They increase their stability by always keeping at least 3 legs in contact with the surface on which they move. When hunting they extend their pedipalps out in front of them. They have the ability to immediately detach one of their legs if pursued by a predator. The detached leg will continue to twitch and is thought to distract the predator and allow escape. Unfortunately, they are not capable of regrowing a leg lost in this way. Predators include birds, mammals, amphibians and spiders.

Although I would rather not see a bee species as prey, in general Harvestmen are regarded as quite beneficial to outdoor and garden environments, keeping down pest species. I did not see the Harvestman catch this bee, so it may have simply found one dead. Harvestmen are omnivorous, catching and eating small insects but also eating some plants and fungi. They also feed on dead material and waste. Young Harvestmen are said to resemble adults, but go through four to eight nymphal stages before they reach maturity at 2-3 months old. Most species live about a year.

They primarily feed on the pollen and nectar of flowers, and honeydew produced by aphids. The adult at right is perching on Buttonbush. Lacewings are members of the order Neuroptera. The order name is Latin for net-wing and refers to the strong venation in the wings. Green Lacewings belong to the family Chrysopidae (gold-faced), referring to the golden eyes of some species. There are 87 species of Green Lacewings in the United States and Canada. Both the adult and larval forms have some clever adaptations to avoid predators. The adults are sensitive to the wavelengths of echolocation emitted by foraging bats, and they will immediately take evasive action if they encounter a bat. They close their wings, making their echolocational signature smaller, and drop to the ground. Tiny hairs on the wings prevent the wings from sticking to spider webs and they do not struggle to get free like most insects. Instead, they quietly bite through any strands of web holding their body or feet and slide free of the web. They also emit a foul odor when attacked. Some species can generate very low frequency sounds by vibrating their abdomen during courtship. These sounds are around 60 hz and delivered once per second to once every few seconds, depending on the species. Some adults overwinter. In the summer months the time from egg to adulthood is only about four weeks. Total lifespan is not much longer, to around six weeks. The tiny white eggs are distinctive, attached to the bottom of leaves and on short (1/2 inch) stalks.

We often find them on the trunks of conifers. Any small patch of lichen should be checked, particularly if it is mostly circular and a little convex and appears to be slightly raised above the bark. You can often find them in the winter months. They are voracious predators. They are sometimes called "aphid lions". Other prey include caterpillars and other insect larvae and eggs. They forage by swinging from side to side, and when they strike a prey item they grasp it. They will sometimes bite a human, and with the jaws visible in the image below, you probably do not want that to happen. The maxillae are hollow, allowing a digestive secretion to be injected into the bite, dissolving the organs of their insect prey in seconds. But they are a good species to have around a garden. Some plant species that have been suggested for attracting lacewings are calliopsis, cosmos, sunflowers and dandelions. The larvae pupate in a cocoon in one to three weeks, depending on environmental conditions. Species from temperate regions usually overwinter in prepupal form, but sometimes overwinter as adults.

Sky Events for July 2023: Morning Sky:

Jupiter

and

Saturn

are both in the morning sky. At the beginning of the month Saturn is in

Aquarius. The tilt of Saturn's rings is decreasing as our perspective of

the rings changes as it orbits the Sun. The next time the rings will

appear edge-on is March 2025. At the beginning of the month look for Saturn due south about 45 minutes before sunrise, about

45 degrees above the horizon. At that time Jupiter will

be about 35 degrees above the eastern horizon in Aries. Evening Sky:

Update July 23rd: Venus is still easy to see, and will be for a few more days. The crescent will be getting larger and thinner. I actually had no trouble finding Venus in 10x30 image-stabilized binoculars and with my naked eye before sunset on July 22nd. Clouds hid the Sun and that probably made it easier to spot. It was 17 degrees above the horizon, about due west. It mirrored the waxing crescent Moon. It looked like a mirror image of the picture above. See how many more days you can keep it in sight. Some tips: Start before sunset, of course keeping your binoculars well away from the Sun, which is about 25 degrees to the north (to your right as you're facing west). Otherwise you could do permanent damage to your eyes. Use a compass and look due west about two fist-widths at arm's length above the true horizon and then scan the area down to the horizon. Start about 20 minutes before local sunset. I spotted it yesterday about 13 minutes before sunset. I was able to spot Venus with the naked eye when I thought to try about 3 minutes later. It's important to spot it as soon as you can, because as it gets darker it the crescent shape becomes harder and harder to see. Unless you have unusually good vision, the crescent shape does not reveal itself to the naked eye. Mars continues to fade and drifts through Leo this month. Look for it above and to the left of Venus in the western sky at dusk. Telescopically the disk of the planet is less than 5 seconds of an arc in apparent diameter, making surface details very difficult to see. In binoculars you should still be able to pick up its reddish tint. Mercury will be low in the west after sunset during the last week of the month. Look for it about 30 to 40 minutes after sunset. Constellations:

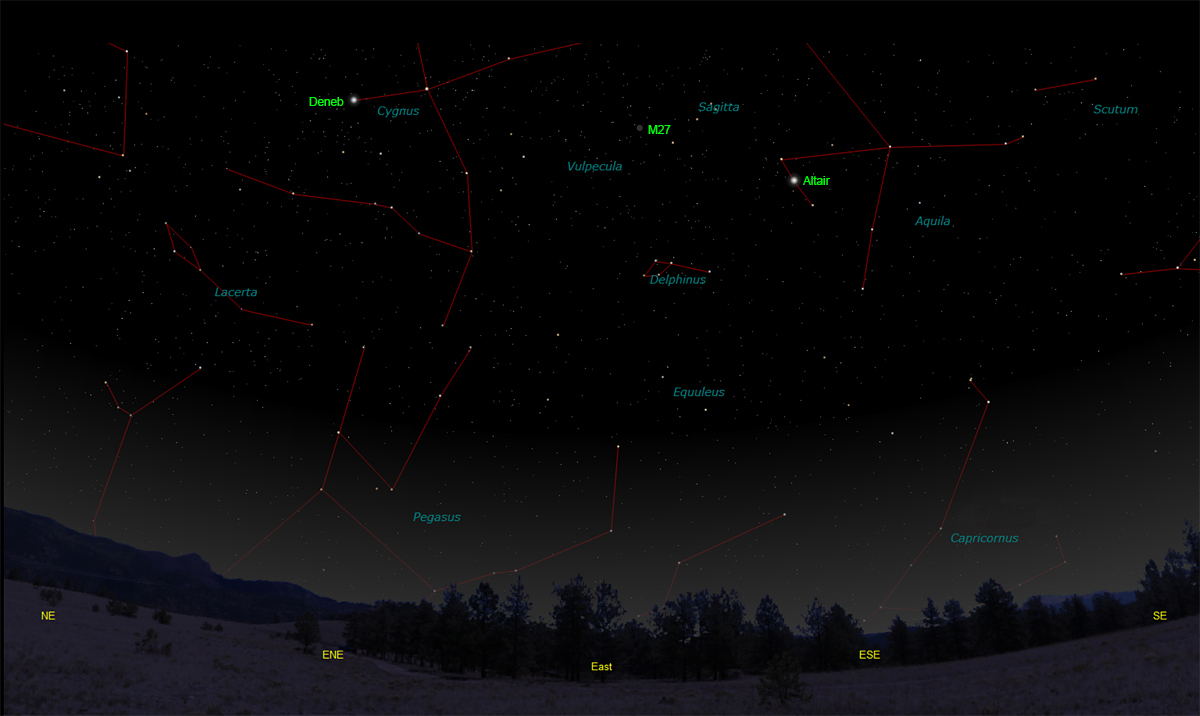

If you look to the south southeast, you will find the little "teapot" asterism that is formed by some of the bright stars of Sagittarius, the Archer. The great star clouds of the Milky Way extend upwards from the spout of the teapot. Just to the right of the spout is the location Sagittarius A* the point that marks the center of our Milky Way Galaxy. The star clouds wind through the constellations of Scutum, Aquilla, Sagitta, Vulpecula and Cygnus, then on through Lacerta and Cassiopeia. Some of the features of the Milky Way, like the Lagoon Nebula, you can see with the naked eye on a clear dark night. Others, like M27, the Dumbbell Nebula in Vulpecula, require binoculars to spot. It can be seen as a fuzzy patch in binoculars (don't expect the bright colors - just a grayish green spot). Use the easy-to-find stars of nearby Sagitta to locate it, using the finder chart here.

On Learning the Constellations: Try learning a few constellations each month, and then following them through the seasons. Once you associate a particular constellation coming over the eastern horizon at a certain time of year, you may start thinking about it like an old friend, looking forward to its arrival each season. The stars in the evening scene above, for instance, will always be in the same place relative to the horizon at the same time and date each July. Of course, the planets do move slowly through the constellations, but with practice you will learn to identify them from their appearance. In particular, learn the brightest stars (like Deneb and Altair in the above scene), for they will guide you to the fainter stars. Once you can locate the more prominent constellations, you can "branch out" to other constellations around them. It may take you a little while to get a sense of scale, to translate what you see on the computer screen or what you see on the page of a book to what you see in the sky. Look for patterns, like the stars that make up the constellation Cygnus. The earth's rotation causes the constellations to appear to move across the sky just as the sun and the moon appear to do. If you go outside earlier than the time shown on the charts, the constellations will be lower to the eastern horizon. If you observe later, they will have climbed higher. As each season progresses, the earth's motion around the sun causes the constellations to appear a little farther towards the west each night for any given time of night. If you want to see where the constellations in the above figures will be on August 15th at 10:30pm EDT, you can stay up till 12:30am EDT on July 16th and get a preview. The westward motion of the constellations is equivalent to two hours per month.

Recommended: Sky & Telescope's Pocket Star Atlas is beautiful, compact star atlas. A good book to learn the constellations is Patterns in the Sky, by Hewitt-White. For sky watching tips, an inexpensive good guide is Secrets of Stargazing, by Becky Ramotowski.

A good general reference book on astronomy is the Peterson

Field Guide,

A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets, by Pasachoff. The book retails for around $14.00.

The Virtual Moon Atlas is a terrific way to learn the surface features of the Moon. And it's free software. You can download the Virtual Moon Atlas here. Apps: The Sky Safari 6 basic version is free and a great aid for the beginning stargazer. We really love the Sky Safari 6 Pro. Both are available for iOS and Android operating systems. There are three versions. The Pro is simply the best astronomy app we've ever seen. The description of the Pro version reads, "includes over 100 million stars, 3 million galaxies down to 18th magnitude, and 750,000 solar system objects; including every comet and asteroid ever discovered." A nother great app is the Photographer's Ephemeris. Great for finding sunrise, moonrise, sunset and moonset times and the precise place on the horizon that the event will occur. Invaluable not only for planning photographs, but also nice to plan an outing to watch the full moon rise. Available for both androids and iOS operating systems.

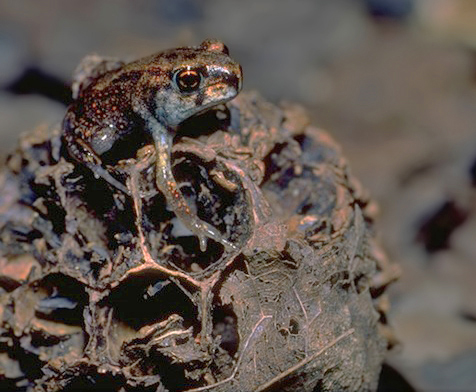

Amphibians:

Recommended: The Frogs and Toads of North America, Lang Elliott, Houghton Mifflin Co. Archives (Remember to use the back button on your browser, NOT the back button on the web page!) Natural Calendar February 2023 Natural Calendar December 2022 Natural Calendar November 2022 Natural Calendar September 2022 Natural Calendar February 2022 Natural Calendar December 2021 Natural Calendar November 2021 Natural Calendar February 2021 Natural Calendar December 2020 Natural Calendar November 2020 Natural Calendar September 2020 Natural Calendar February 2020 Natural Calendar December 2019 Natural Calendar November 2019 Natural Calendar September 2019 Natural Calendar February 2019 Natural Calendar December 2018 Natural Calendar November 2018 Natural Calendar September 2018 Natural Calendar February 2018 Natural Calendar December 2017 Natural Calendar November 2017 Natural Calendar October 2017Natural Calendar September 2017 Natural Calendar February 2017 Natural Calendar December 2016 Natural Calendar November 2016 Natural Calendar September 2016Natural Calendar February 2016 Natural Calendar December 2015 Natural Calendar November 2015 Natural Calendar September 2015 Natural Calendar November 2014 Natural Calendar September 2014 Natural Calendar September 2013 Natural Calendar December 2012 Natural Calendar November 2012 Natural Calendar September 2012 Natural Calendar February 2012 Natural Calendar December 2011 Natural Calendar November 2011 Natural Calendar September 2011 Natural Calendar December 2010 Natural Calendar November 2010 Natural Calendar September 2010 Natural Calendar February 2010 Natural Calendar December 2009 Natural Calendar November 2009 Natural Calendar September 2009 Natural Calendar February 2009 Natural Calendar December 2008 Natural Calendar November 2008 Natural Calendar September 2008 Natural Calendar February 2008 Natural Calendar December 2007 Natural Calendar November 2007 Natural Calendar September 2007 Natural Calendar February 2007 Natural Calendar December 2006 Natural Calendar November 2006 Natural Calendar September 2006 Natural Calendar February 2006

Natural Calendar December 2005

Natural Calendar November 2005

Natural Calendar September 2005

Natural Calendar February 2005

Natural Calendar December 2004

Natural Calendar November 2004

Natural Calendar September 2004

Natural Calendar February 2004

Natural Calendar December 2003

Natural Calendar November 2003 Natural Calendar February 2003 Natural Calendar December 2002 Natural Calendar November 2002 Nature Notes Archives: Nature Notes was a page we published in 2001 and 2002 containing our observations about everything from the northern lights display of November 2001 to frog and salamander egg masses. Night scenes prepared with The Sky Professional from Software Bisque All images and recordings © 2023 Leaps

|

|