The purpose of this feature is to give scout leaders, educators and naturalists an idea of some of the natural events coming up each month. We will try to cover a variety of natural events ranging from sky events to calling periods of amphibians, bird and mammal watching tips, prominent wildflowers and anything else that comes to mind. We will also note prominent constellations appearing over the eastern horizon at mid-evening each month for our area for those who would like to learn the constellations. If you have suggestions for other types of natural information you would like to see added to this calendar, let us know! Note: You can click on the hyperlinks to learn more about some of the featured items. To return to the Calendar, hit the "back" button on your browser, NOT the "back" button on the web page. All charts are available in a "printer friendly" mode, with black stars on a white background. Left clicking on each chart will take you to a printable black and white image. Please note that images on these pages are meant to be displayed at 100%. If your browser zooms into a higher magnification than that, the images may lose quality. Though we link book references to nationwide sources, we encourage you to support your local book store whenever possible.

Notes and Images From January 2010 On July 4th, 1054AD, a brilliant new star appeared in the constellation of Taurus, the Bull. In the early morning hours of July 5th it blazed beneath a slender crescent moon. According to Chinese records the "guest star" was six times brighter than the planet Venus and was visible in the daytime sky for 23 days. Native American pictographs in Chaco Canyon are thought to depict the event. The new star was visible in the evening sky for almost two years before it faded from view. For the next 700 years, nothing else was noted concerning the guest star. Then, in 1731, a physician and amateur astronomer named John Bevis spotted a small faint patch of nebulosity near zeta Taurus, which marks the tip of one of the bull's horns. He noted it on the star atlas he was preparing. Click here to see a detail of the atlas courtesy of the Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology. Charles Messier independently discovered the nebula 27 years later in 1758. Messier was searching for the comet predicted by Edmund Halley to return that year, and which now bears Halley's name. While searching for the comet, he spotted the same small patch of nebulosity that Bevis had seen. Messier initially thought he had recovered the comet, but when the nebulous object didn't change position relative to the stars, he knew he had been fooled. So this wouldn't happen again, he began a catalog of objects that were comet look-alikes. The nebula in Taurus became Messier 1, the first object in his new catalog. Lord Rosse observed the nebula in 1844. Using the large Newtonian reflector at Birr Castle in Ireland, he thought the nebula resembled a Horseshoe Crab. Hence the popular name of the Crab Nebula. It would be another 77 years before anyone connected the nebula to the brilliant star that appeared in 1054AD. In 1921, studies of photographs taken over a period of time showed a small but definite expansion of the nebula. Working backward, it was calculated that the nebula would have expanded from a point source around 900 years prior. It was Knut Lundmark who first noted the close proximity of Messier 1 to the bright star of 1054AD. The "guest star" of 1054 AD had been a supernova. A star with a mass between 9 and 11 solar masses had reached the end of its life and exploded, leaving behind a cloud of debris and an incredibly dense core known as a neutron star. In the collapsed core, the mass of between 1 and 2 Suns is compressed into a sphere only 15 miles in diameter. The material of the star is so dense that one teaspoon of the star's material would weigh 12 trillion pounds. Or, to put it another way, imagine squeezing the entire mass of the Earth - it's mountains, deserts, seas and cities - into a sphere slightly over 1000 feet in diameter. Then set it spinning as fast as the crankshaft of an idling tractor.

In 1949 Messier 1 was discovered to be a strong source of radio waves, and in 1959 it was found to be a powerful source of X-rays. In 1967, Jocelyn Bell, an English graduate student doing research with a radio telescope on quasars, discovered a new type of rapidly pulsating star. The new stars became known as pulsars. Soon afterward, a pulsar was discovered in the Crab Nebula. The neutron star at the center of the crab spins at a rate of 30.2 revolutions per second, and its incredibly strong magnetic field channels a beam of photons outward from each pole of the magnetic field. The Earth happens to be in the path of one of these beams, and the beam sweeps past the Earth 30.2 times per second. Bell and her colleagues named the first two pulsars LGM-1 and LGM-2. The letters stood for little green men, a tongue in cheek reference to the precise spacing of the signals. You can learn more about pulsars and hear Jocelyn Bell Burnell tell in her own words the story of one of the greatest discoveries of the 20th century here. To see and learn more about the crab nebula's pulsar, including a composite x-ray and Hubble Space Telescope optical wavelength video clip, a "Lucky Imaging" video of the pulsar pulsing, and telescope finder charts, click here.

Sky Events for February 2010: Evening Sky: Although visible very low in the southwest at dusk at the beginning of the month, Jupiter will disappear into the twilight by the end of the month. Venus is not visible at the beginning of the month, but steadily rises higher each day in the southwest at dusk as the month progresses. The two planets pass on the 16th, coming within about a half of a degree of each other. Two evenings earlier, on January 14th, the two planets are close to an extremely thin crescent Moon which is less than 24 hours old. You will want binoculars to try to see it. Wait until the sun goes down, then scan just up and to the left of the point where the sun went down. The very thin crescent will form a triangle with Jupiter and Venus.

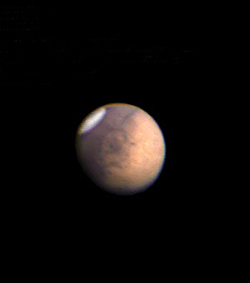

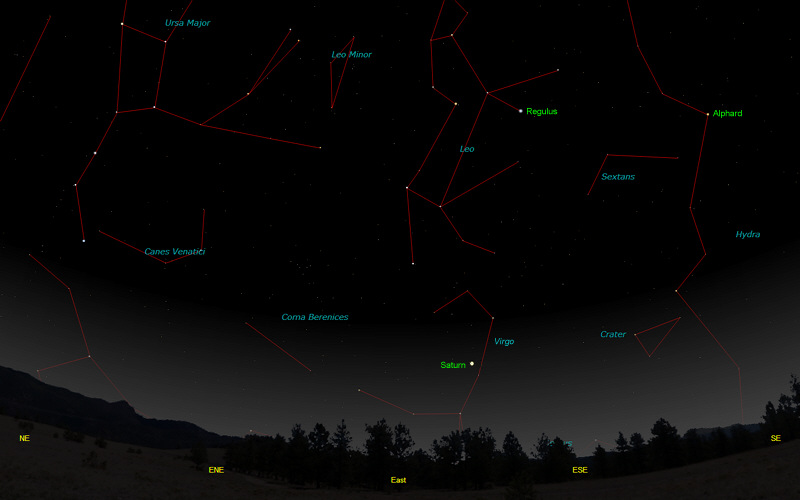

Mars rises at dusk in Cancer at the beginning of the month. The red planet still is very bright after its closest approach to Earth on January 29th, and good telescopic views are still possible. For binocular and naked eye viewers, it passes by the Beehive Cluster on the evening of February 4th. Sky and Telescope has a "Mars Profiler" online that shows which face of Mars is facing Earth at any given time. This can be very helpful, and you may want to choose a time to observe when a darker area like Syrtis Major is in the center of the disk. When asked for the time in Universal Time (UT), add 6 hours to Central Standard Time in 24 hour format. For instance, 5:00pm CST on February 1st would be 17:00 hours in a 24 hour format. This would equate to 17 + 6 = 23:00 hours UT on February 1st. Note that for later times in the evening the Universal Time will be on the following day. For example,10:00pm on February 1st would be 22:00 hours in a 24 hour format. Adding 6 hours will give you 28:00 hours, or 04:00 hours UT on February 2nd. To go to the Mars Profiler, click here. For more about the surface features of Mars, see the January, 2010 Natural Calendar. Saturn rises around 9:00pm CST at at the beginning of the month in Virgo. Morning Sky: Look for Mercury low in the morning sky about 30 to 40 minutes at the beginning of February. The planet should be about 7 degrees above the southeastern horizon. It will gradually sink back into the twilight glow as the month goes on. All times noted in the Sky Events are for Franklin, Tennessee and are Central Standard Time. These times should be pretty close anywhere in the mid-state area. Constellations: The views below show the sky looking east at 9:30pm CST on February 15th. The first view shows the sky with the constellation outlines and names depicted. Star and planet names are in green. Constellation names are in blue. The second view shows the same scene without labels. Leo, the Lion, is prominent with its bright star Regulus. Look above the eastern horizon for the bright planet Saturn. Use Regulus and Saturn to guide you to the faint constellation of Sextans, the Sextant. Conspicuous in the northeast is Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The constellations of Coma Berenices, Berenice's Hair, Virgo, the Virgin and Crater, the Cup are all just making their way above the horizon and will be seen better next month. If you can't wait, you can always stay up a little later and watch them as they climb higher above the horizon.

On Learning the Constellations: We advise learning a few constellations each month, and then following them through the seasons. Once you associate a particular constellation coming over the eastern horizon at a certain time of year, you may start thinking about it like an old friend, looking forward to its arrival each season. The stars in the evening scene above, for instance, will always be in the same place relative to the horizon at the same time and date each February. Of course, the planets do move slowly through the constellations, but with practice you will learn to identify them from their appearance. In particular, learn the brightest stars (like Regulus in the above scene looking east), for they will guide you to the fainter stars. Once you can locate the more prominent constellations, you can "branch out" to other constellations around them. It may take you a little while to get a sense of scale, to translate what you see on the computer screen or what you see on the page of a book to what you see in the sky. Look for patterns, like the stars of the "Big Dipper." The earth's rotation causes the constellations to appear to move across the sky just as the sun and the moon appear to do. If you go outside earlier than the time shown on the charts, the constellations will be lower to the eastern horizon. If you observe later, they will have climbed higher. As each season progresses, the earth's motion around the sun causes the constellations to appear a little farther towards the west each night for any given time of night. If you want to see where the constellations in the above figures will be on March 15th at 9:30pm CST, you can stay up till 11:30pm CST on the February 15th and get a preview. The westward motion of the constellations is equivalent to two hours per month. For instance, if you want to see what stars will be on your eastern horizon on May 15th at 9:30pm CST (3 months from now), you would need to get up at 3:30am CST on February 15th (3 months times 2 hours/month = 6 hours). Recommended: Sky & Telescope's Pocket Star Atlas is beautiful, compact star atlas. It is destined to become a classic, and is a joy to use at the telescope. A good book to learn the constellations is Patterns in the Sky, by Hewitt-White. You may also want to check out at H. A. Rey's classic, The Stars, A New Way to See Them. For skywatching tips, an inexpensive good guide is Secrets of Stargazing, by Becky Ramotowski. A good general reference book on astronomy is the Peterson

Field Guide,

A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets, by Pasachoff. The book retails for around $14.00. Starry Night has several software programs for learning the night sky. Visit the Starry Night web site at www.starrynight.com for details.

Amphibians:

The amphibian season continues to build in February. One trick to finding amphibians in winter is to go out on mild (50 degrees Fahrenheit or warmer) rainy nights. For safety, it is important that you have another person with you to help watch for traffic as you slowly drive the back roads. Look for things that cross the road in front of you and stop frequently and listen. Early breeding frogs like Upland Chorus Frogs, Spring Peepers and Wood Frogs are already calling by the first of the month. On warmer nights listen for Southern Leopard Frogs. Spotted Salamanders and Tiger Salamanders also breed in January and February, and the eggs of both can often be found this time of year. Towards the end of the month, given mild temperatures, you can sometimes hear American Toads beginning to call. In west Tennessee, Crawfish Frogs give their loud snoring calls starting in late February and continuing on into early March. At higher elevations, listen for Mountain Chorus Frogs towards the end of the month. Remember that on mild nights you may find frogs and toads out foraging that you do not hear until later in the season.

Birds: Many times when we have been out looking for amphibians in February we've witnessed courtship flights of the American Woodcock. Listen for the "peent" call at dusk and watch as the male Woodcock spirals upward till it's almost out of sight, then dives back to the ground, twisting and turning. For more about watching American Woodcocks see, "The Woodcock's Call." Red-Shouldered Hawks mate as early as February in Tennessee. Watch for courtship activities of these and other hawks. Stick Nests: With the leaves down, this is a great time of year to find raptor stick nests. I make notes of all the nests I find and then periodically check them to see if anyone has "moved in." Many times Great Horned Owls make use of an old Red-Tailed Hawk's nest from the previous year. The owls can already be incubating eggs in January. Of the hawks, Arthur Cleveland Bent, in his "Life Histories of North American Birds of Prey," writes, "[Red-tailed Hawks]...begin their nest building late in February or early in March; I have seen a wholly new nest half completed and decorated with green pine twigs and down as early as February 18th, over a month before the eggs are laid...Typical nests are from 28 to 30 inches in outside diameter, the inner cavity being 14 or 15 inches wide and 4 or 5 inches deep...The nests are well made of sticks and twigs, half an inch or less in thickness, and neatly lined with strips of inner bark, of cedar, grapevine or chestnut, usnea, and usually at least a few green sprigs of pine, cedar or hemlock. Some nests are profusely and beautifully lined with fresh green sprigs of white pine, which are frequently renewed during incubation and during the earlier stages of growth of the young...They "stake out their claim" late in February or early in March...by marking the nest they propose to use with a sprig of green pine...I believe that the birds prefer to build a new nest each year, but they sometimes use the same nest for consecutive years..." Bent was writing about the Red-Tail Hawks in New England, so our times could be a little earlier. You probably have already put out your bird feeders, but if you havenít you're missing out on a lot of good looks at winter feeder birds. This is a great time of year to start learning your birds. Watch and listen for winter residents such as White-throated and White-crowned Sparrows, Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers, Red-breasted Nuthatches, Golden-crowned Kinglets and Brown Creepers. Recommended: The Sibley Guide to Birds, David Allen Sibley The Sibley Guide to Birds of Eastern North America, David Allen Sibley An inexpensive guide for beginners is the Golden Guide for Birds.

Archives (Remember to use the back button on your browser, NOT the back button on the web page!) Natural Calendar December 2009 Natural Calendar November 2009 Natural Calendar September 2009 Natural Calendar February 2009 Natural Calendar December 2008 Natural Calendar November 2008 Natural Calendar September 2008 Natural Calendar February 2008 Natural Calendar December 2007 Natural Calendar November 2007 Natural Calendar September 2007 Natural Calendar February 2007 Natural Calendar December 2006 Natural Calendar November 2006 Natural Calendar September 2006 Natural Calendar February 2006

Natural Calendar

December 2005

Natural Calendar

November 2005

Natural Calendar

September 2005

Natural Calendar

February 2005

Natural Calendar

December 2004

Natural Calendar

November 2004

Natural Calendar

September 2004

Natural Calendar

February 2004

Natural Calendar

December 2003

Natural Calendar

November 2003

Natural Calendar

September 2003 Natural Calendar February 2003 Natural Calendar December 2002 Natural Calendar November 2002 Nature Notes Archives: Nature Notes was a page we published in 2001 and 2002 containing our observations about everything from the northern lights display of November 2001 to frog and salamander egg masses.

Night scenes prepared with The Sky Professional from Software Bisque All images and recordings © 2010 Leaps |

||||||||