The purpose of this feature is to give scout leaders, educators and naturalists an idea of some of the natural events coming up each month. We will try to cover a variety of natural events ranging from sky events to calling periods of amphibians, bird and mammal watching tips, prominent wildflowers and anything else that comes to mind. We will also note prominent constellations appearing over the eastern horizon at mid-evening each month for our area for those who would like to learn the constellations. If you have suggestions for other types of natural information you would like to see added to this calendar, let us know! Though we link book references to nationwide sources, we encourage you to support your local bookstore whenever possible.

Notes From August 2023 What a summer! August days were hot and steamy, with a large dose of summer thunderstorms. The last week of the month was slightly better, but there was always a chance of a stray thunderstorm popping up, night or day. I managed to protect the telescope from the storms except for one day when my audible approaching-rain alarm was inadvertently turned off. Suddenly I was racing out to the telescope with a tarp in my hand as the skies opened up and rain poured down. I knelt beside the scope and held the tarp over it until the downpour ceased. Luckily the electronics were not turned on and the scope escaped serious damage. My astrophotography cameras like this weather even less than I do. The camera sensors are thermoelectrically cooled, but on warm nights the cameras struggle to get the sensor temperature down to a level that keeps the images from being too noisy. My astrophotography target this month was a supernova remnant in the constellation of Cassiopeia. Although the remnant appears as big as a full moon in the sky, it is incredibly faint. It appeared only when I was using narrowband filters, and was completely invisible with exposures made with normal broad-band red, green and blue filters. In the image below, ionized hydrogen (hydrogen alpha) appears red and ionized oxygen (oxygen III) appears blue. The nebula is around 10,000 light-years distant and is around 100 light-years in diameter.

When a star becomes a supernova, it blows off its outer layers. The shock wave of expanding radiation from the blast ionizes the surrounding gases and the shock wave appears as a shell around the exploding star. What happens to what remains of the star depends on the star's original mass. If the original mass of the star is between 10 and 25 solar masses, the star will form a neutron star. If the original mass exceeds 25 solar masses, the star will collapse into a black hole.

The discovery of pulsars was one of the greatest scientific discoveries of the 20th century. To hear Jocelyn Bell Burnell speak in her own words about her discovery, and her struggle to receive recognition for her work, go here: Journeys of Discovery: Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Pulsars - YouTube. The nebula's name, the Medulla Nebula, refers to the brain-like shape of the nebula. It also to me suggests some rare species of deep water jellyfish, or a creature seen under a microscope in a drop of water. It's also called Abell 85, CTB-1 and the Popped Balloon Nebula. That brings us to what struck me about the nebula when I first went through the images. The nebula looked like it had been punctured by something at the 10:00 o'clock position in my image. What was going on? After a bit of searching I came across the answer. Some supernovae can involve forces that are asymmetric, and that can propel the remaining neutron star or pulsar completely out of the nebula. That was just what had happened with the Medulla Nebula. The central star had collapsed to a pulsar and been hurled out of the nebula, punching a large hole in the ionizing shock wave. We are not talking about small forces here. You are accelerating a twelve-mile diameter object with more mass than our Sun to a speed approaching 2,500,000 miles per hour. That's one heck of a fastball! Its high speed will cause it to exit our galaxy. By chance the object that I imaged was one that had been studied at gamma-wave wavelengths by NASA's Fermi satellite and the National Science Foundation's Very Large Array (VLA). Even more interesting to me was that, as detailed here, the original discovery of the Medulla Nebula pulsar was made in 2017 by citizen scientists working for the NASA-sponsored Einstein@Home project. The project has resulted in the discoveries of 23 pulsars so far. As explained on the Einstein@Home page, the project "uses your computer's idle time to search for weak astrophysical signals for from spinning neutron stars (often called pulsars) using data from the LIGO gravitational -wave detectors, the MeerKAT radio telescope, the Fermi gamma-ray satellite, as well as archival data from the Arecibo radio telescope." What a great project!

Sky Events for September 2023: The September Equinox occurs at 2:50am on September 23rd, marking the beginning of fall in the Northern Hemisphere. Morning Sky:

Update (09/05/23):

Using the finder chart link above I located Comet Nishimura on September

3rd. It appeared as a small fuzzy spot in the 10x30 binoculars, with no

tail visible. Of course, visibilty was compromised due to the low altitude

above the horizon and the waning gibbous Moon, but it was still fun to

track it down. It will be nearest to Earth on September 12th. It could

reach naked eye visibility then.

Mercury

will begin

to be visible low in the east sometime after the first week of September.

It will reach greatest elongation from the Sun on September 22nd. Try to

be at your observing spot about 45 minutes before sunrise. You will want

to have a low eastern horizon. Binoculars will help you spot it.

Venus

is rapidly moving up into the morning sky! As

with Mercury, start observing 30 to 40 minutes before sunrise. Keep

watching as the sky brightens! You will be able to see the thin crescent much better if you keep

following the planet in binoculars (pick out a ground feature for

reference) until you can see it against a fairly bright sky.

Update (09/5/23):

The crescent was stunning in my 10x30

and 12x36 binoculars on the morning of September 3rd. As stated above the

trick is to find the planet early, about 30 to 40 minutes after sunrise.

Against a dark sky the crescent is hard to see due to Venus being so

bright. It shows every defect in your optics and in your eyes! But don't

stop there! Move around until you have Venus over a stationary landmark

like a tree or the corner of a building. Mark where you are standing and

come back at intervals every 10 minutes or so. Each time that you come

back Venus will be higher in the sky. The sky will be brighter, making

Venus a little harder to spot (but you know where to look) but the

crescent shape will be much easier to see. On September 3rd my best and

final view was at 7:51am, a full 50 minutes after sunrise! Needless to

say, keep your binoculars well away from the Sun to avoid permanent eye

damage.

Evening Sky:

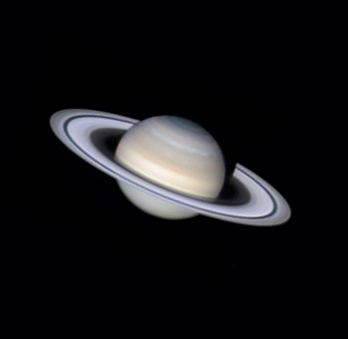

Saturn

rises about sunset but it will take some time for it to become visible in

the evening twilight. You will get better telescopic views later in the

evening. On September 1st it will be up and to the right of the waning

gibbous Moon. September should be a great month to get a view of the

planet in any sized telescope.

Jupiter

will rise about three hours after the sun at the beginning of the month.

It will remain in Aries this month. Constellations:

The views below show the sky looking east at 10:45pm EDT on September 15th. The first view shows the sky with the constellations outlined and names depicted. Star and planet names are in green. Constellation names are in blue. The second view shows the same scene without labels. In Andromeda, see if you can pick out the soft oval glow of the Andromeda Galaxy. It's shown on the chart below. If you have a fairly dark sky it should be visible. Don't expect to see any colors or features with the naked eye. If you succeed in spotting it, you'll be seeing an object that's about 2.5 million light-years distant! Small telescopes may allow you to pick out the two brightest satellite galaxies of the Andromeda Galaxy . These are NGC 205 (visible below the galaxy in the image at above) and NGC 221 (visible above and to the left of the core). Your best chance to see them will be when the galaxy is high overhead.

On Learning the Constellations: We advise learning a few constellations each month, and then following them through the seasons. Once you associate a particular constellation coming over the eastern horizon at a certain time of year, you may start thinking about it like an old friend, looking forward to its arrival each season. The stars in the evening scene above, for instance, will always be in the same place relative to the horizon at the same time and date each September. Of course, the planets do move slowly through the constellations, but with practice you will learn to identify them from their appearance. In particular, learn the brightest stars for they will guide you to the fainter stars. Once you can locate the more prominent constellations, you can "branch out" to other constellations around them. It may take you a little while to get a sense of scale, to translate what you see on the computer screen or cell phone to what you see in the sky. Look for patterns, like the stars that make up the "Square of Pegasus." The earth's rotation causes the constellations to appear to move across the sky just as the Sun and the Moon appear to do. If you go outside earlier than the time shown on the charts, the constellations will be lower to the eastern horizon. If you observe later, they will have climbed higher. As each season progresses, the earth's motion around the sun causes the constellations to appear a little farther towards the west each night for any given time of night.

Recommended: Sky & Telescope's Pocket Star Atlas is beautiful, compact star atlas. A good book to learn the constellations is Patterns in the Sky, by Hewitt-White. For sky watching tips, an inexpensive good guide is Secrets of Stargazing, by Becky Ramotowski.

A good general reference book on astronomy is the Peterson

Field Guide,

A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets, by Pasachoff. The book retails for around $14.00.

The Virtual Moon Atlas is a terrific way to learn the surface features of the Moon. And it's free software. You can download the Virtual Moon Atlas here. Apps: The Sky Safari 6 basic version is free and a great aid for the beginning stargazer. We really love the Sky Safari 6 Pro. Both are available for iOS and Android operating systems. There are three versions. The Pro is simply the best astronomy app we've ever seen. The description of the Pro version reads, "includes over 100 million stars, 3 million galaxies down to 18th magnitude, and 750,000 solar system objects; including every comet and asteroid ever discovered." A nother great app is the Photographer's Ephemeris. Great for finding sunrise, moonrise, sunset and moonset times and the precise place on the horizon that the event will occur. Invaluable not only for planning photographs, but also nice to plan an outing to watch the full moon rise. Available for both androids and iOS operating systems.

Amphibians:

At the beginning of September you often hear just a few Green Frogs and Bullfrogs calling. But if cooler weather arrives (we hope) you can pick up several other species.

Spring Peepers

are also know as "Autumn Pipers" and can be heard calling from patches of

woods during the fall. Listen also for the very dry and scratchy

version of the Upland Chorus Frog's song on rainy fall evenings.

Cooler weather can also bring out choruses of

Southern Leopard Frogs. They

do occasionally breed in the fall as well. You can sometimes find the eggs of Marbled Salamanders in wooded wetlands in the fall. Recommended: The Frogs and Toads of North America, Lang Elliott, Houghton Mifflin Co. Archives (Remember to use the back button on your browser, NOT the back button on the web page!) Natural Calendar February 2023 Natural Calendar December 2022 Natural Calendar November 2022 Natural Calendar September 2022 Natural Calendar February 2022 Natural Calendar December 2021 Natural Calendar November 2021 Natural Calendar February 2021 Natural Calendar December 2020 Natural Calendar November 2020 Natural Calendar September 2020 Natural Calendar February 2020 Natural Calendar December 2019 Natural Calendar November 2019 Natural Calendar September 2019 Natural Calendar February 2019 Natural Calendar December 2018 Natural Calendar November 2018 Natural Calendar September 2018 Natural Calendar February 2018 Natural Calendar December 2017 Natural Calendar November 2017 Natural Calendar October 2017Natural Calendar September 2017 Natural Calendar February 2017 Natural Calendar December 2016 Natural Calendar November 2016 Natural Calendar September 2016Natural Calendar February 2016 Natural Calendar December 2015 Natural Calendar November 2015 Natural Calendar September 2015 Natural Calendar November 2014 Natural Calendar September 2014 Natural Calendar September 2013 Natural Calendar December 2012 Natural Calendar November 2012 Natural Calendar September 2012 Natural Calendar February 2012 Natural Calendar December 2011 Natural Calendar November 2011 Natural Calendar September 2011 Natural Calendar December 2010 Natural Calendar November 2010 Natural Calendar September 2010 Natural Calendar February 2010 Natural Calendar December 2009 Natural Calendar November 2009 Natural Calendar September 2009 Natural Calendar February 2009 Natural Calendar December 2008 Natural Calendar November 2008 Natural Calendar September 2008 Natural Calendar February 2008 Natural Calendar December 2007 Natural Calendar November 2007 Natural Calendar September 2007 Natural Calendar February 2007 Natural Calendar December 2006 Natural Calendar November 2006 Natural Calendar September 2006 Natural Calendar February 2006

Natural Calendar December 2005

Natural Calendar November 2005

Natural Calendar September 2005

Natural Calendar February 2005

Natural Calendar December 2004

Natural Calendar November 2004

Natural Calendar September 2004

Natural Calendar February 2004

Natural Calendar December 2003

Natural Calendar November 2003 Natural Calendar February 2003 Natural Calendar December 2002 Natural Calendar November 2002 Nature Notes Archives: Nature Notes was a page we published in 2001 and 2002 containing our observations about everything from the northern lights display of November 2001 to frog and salamander egg masses. Night scenes prepared with The Sky Professional from Software Bisque All images and recordings © 2023 Leaps

|

|