|

Back

An Occultation of Saturn

Sometimes the most enjoyable natural events are the ones we don’t expect.

Wednesday, February 20th, dawned gray and cloudy. Although we knew

the moon was going to be passing in front of Saturn that evening, we thought we

had little chance of seeing the event due to clouds. The computer predicted

that in Franklin, the first quarter moon’s unlit side should begin to hide the

planet about 5:53pm. About 5:45pm Andrea told me there were some breaks in the

cloud cover. We rushed downstairs and grabbed our 6” Dobsonian reflecting

telescope and dashed outside. The little Dobsonian is simplicity itself. To

set it up, one of us grabs the tube assembly and the other grabs the base.

Setup consists of plopping the base on the ground and setting the tube assem

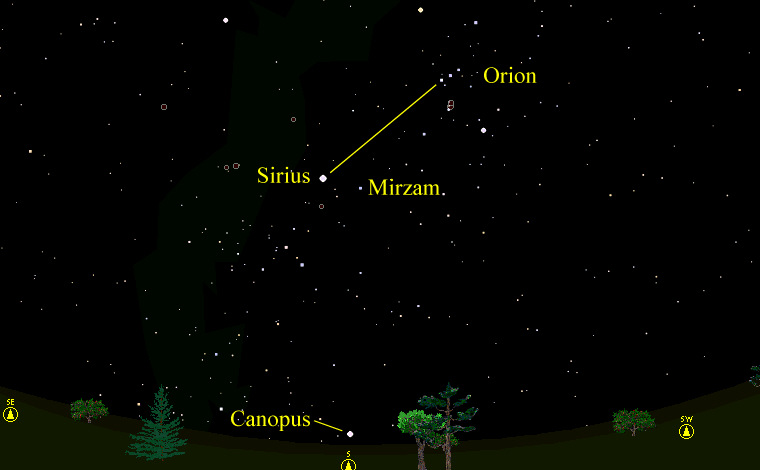

A Southern Beacon The bright star Canopus is like a lighthouse in the southern sky. Seventy-five times larger than our sun, its light output exceeds the sun's by a factor of 20,000. It is the second brightest star in the nighttime sky. Only Sirius, in Canis Major, is brighter. Canopus is the brightest star in the constellation of Carina, which forms the keel of the celestial ship (formerly a constellation) Argo Navis. To see this star directly overhead you would have to go Cape Horn, on the extreme southern tip of SouthAmerica. Because Canopus is located so far south, we rarely see it above the horizon at our latitude. These clear winter evenings you can try to spot Canopus as it arcs over the southern horizon with as little clearance as a high jumper clearing a 7-foot bar. The primary requirements are a clear night and a very flat southern horizon. Fortunately, Canopus is so bright that is will shine through some haze and thin clouds. This week I drove down to a spot near Eagleville, Tennessee and saw Canopus near the top of its arc, about one and one half degrees above the horizon. To try to see Canopus, print out a finder chart of the figure below. Face south (a compass is helpful if you’re not used to orienting yourself by the North Star) about 7:30pm and locate the constellation of Orion.

This constellation is usually easy to pick out because it’s bright and the three distinctive stars of Orion’s belt make an easy pattern to spot. The three “belt” stars point to Sirius, the brightest star in the nighttime sky. Hold up your hand at arms length and look three fingers to the right of Sirius for the star Mirzam. Look for Canopus when Mirzam is due south (about 7:50pm on this date). Canopus will be just above the horizon and directly beneath Mirzam. Binoculars will make it easier to spot, although on a clear night it may be easy to see with the naked eye. How far north can Canopus be spotted over the horizon? Calculations place its northern limit of visibility about the latitude of the Kentucky cities of Madisonville, Paducah and Hazard. This, however, does not take into account the effect of atmospheric refraction, which tends to “lift” the image of the rising star about another half a degree*. Because of this lifting effect, Canopus may be able to be seen farther north. We would like to hear from you if you’re able to see Canopus. Let us know (contact us) the date and time of your sighting, the location, sky conditions, elevation and anything else you think would be helpful. We would be especially interested in Kentucky sightings. Who can sight it from the most northerly location? We’ll publish the results in a future “Nature Notes.” *Because of atmospheric refraction, when we see the lower edge of the rising or setting sun touching the horizon, the sun is actually just below the horizon. We can still see it only because of the bending of the suns rays by our atmosphere.

Young Great Horned OwlsLate February and March is a good time to look and listen for young Great Horned Owls. Great Horned Owls nest quite early and can have young owls on the nest by now.

Walking good habitat (perhaps where you’ve heard them call) and listening at dusk and dawn for the scratchy “begging” cries of the young owls may give you a great look at a young owl. Do not get too close to them. If an adult is nearby, this could be hazardous to your health! Often these owls are found by themselves with no parent visible. Sometimes the young owls are on the ground or a low branch. This is natural and you can be assured that the young owl will be fed by the parent after you leave. Far too many young owls are taken from the wild by well meaning individuals who think the owls have been abandoned or have fallen from a nest. If you take an uninjured owl from the wild you may be condemning it to either a lifetime in captivity or a very short life after it is released. Instead, watch respectfully from a distance.

The Frog YearThere are many frogs calling now. January brings us calling Upland Chorus Frogs, Spring Peepers, Wood Frogs and Southern Leopard Frogs. Joining them in February are American Toads, Mountain Chorus Frogs and Northern Crawfish Frogs. By March other species like Gray Treefrogs and Bullfrogs may begin calling. It’s an exciting time of year – keep listening! Young Great Horned Owl photograph © 1999 LEAPS Simulated night views created with Starry Night Software

|

bly

on top of it. I also grabbed an eyepiece and Barlow lens. Total setup time –

maybe a minute. The Dobsonian mount has no clock drive to track the stars and

planets as the earth’s rotation carries them across the field. This means that

every so often you must nudge the telescope to follow a planet or star. We took

turns watching as the dark limb of the moon bit into the rings and moved across

the globe of Saturn. Clouds moved across the field as we watched, the view

fading out and then returning. The sky events were accompanied by the sounds of

Upland Chorus Frogs and Southern Leopard Frogs calling from our pond, and

occasionally the “peent” of a woodcock from the field across the railroad

tracks. We returned about 7:20pm to watch for Saturn’s emergence. The moonlit

clouds were racing across the sky now and the bright limb of the moon through

the telescope alternately disappeared and then came flashing back. Between the

clouds we caught glimpses of dark sky. The star colors there seemed to be

intensified. The bright star Betelgeuse in the shoulder of Orion glowed like a

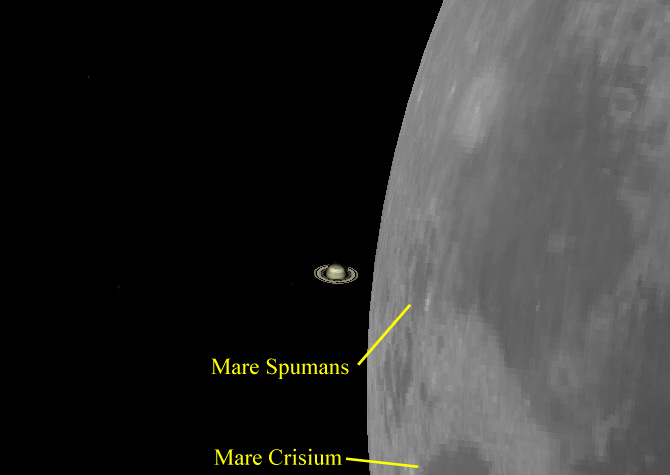

small red coal. We concentrated our search for Saturn around Mare Spumans, the

Foaming Sea, a small lunar “sea” near the larger Mare Crisium, the Sea of

Crises. Then, there they were. The rings slowly emerged from behind the moon

and for a few minutes we savored the view of Saturn, so far away, beside the

bright limb of the moon, so close. Then, with the celebrations of the chorus

frogs still drifting up from the pond, we left the moon and Saturn to continue

their journeys and, feeling very fortunate, went back inside.

bly

on top of it. I also grabbed an eyepiece and Barlow lens. Total setup time –

maybe a minute. The Dobsonian mount has no clock drive to track the stars and

planets as the earth’s rotation carries them across the field. This means that

every so often you must nudge the telescope to follow a planet or star. We took

turns watching as the dark limb of the moon bit into the rings and moved across

the globe of Saturn. Clouds moved across the field as we watched, the view

fading out and then returning. The sky events were accompanied by the sounds of

Upland Chorus Frogs and Southern Leopard Frogs calling from our pond, and

occasionally the “peent” of a woodcock from the field across the railroad

tracks. We returned about 7:20pm to watch for Saturn’s emergence. The moonlit

clouds were racing across the sky now and the bright limb of the moon through

the telescope alternately disappeared and then came flashing back. Between the

clouds we caught glimpses of dark sky. The star colors there seemed to be

intensified. The bright star Betelgeuse in the shoulder of Orion glowed like a

small red coal. We concentrated our search for Saturn around Mare Spumans, the

Foaming Sea, a small lunar “sea” near the larger Mare Crisium, the Sea of

Crises. Then, there they were. The rings slowly emerged from behind the moon

and for a few minutes we savored the view of Saturn, so far away, beside the

bright limb of the moon, so close. Then, with the celebrations of the chorus

frogs still drifting up from the pond, we left the moon and Saturn to continue

their journeys and, feeling very fortunate, went back inside.