|

Note July, 2006: I wrote this page in June of 2002. Since then I’ve found out that many birds have color vision that far exceeds that of all mammals, including humans, in both the amount of the spectrum that is visible and in the richness of the colors they see. A particularly interesting article appears in this month’s issue (July, 2006) of Scientific American, entitled, “What Birds See.” Delighted ducks, indeed! Somewhere Over Roy G Biv

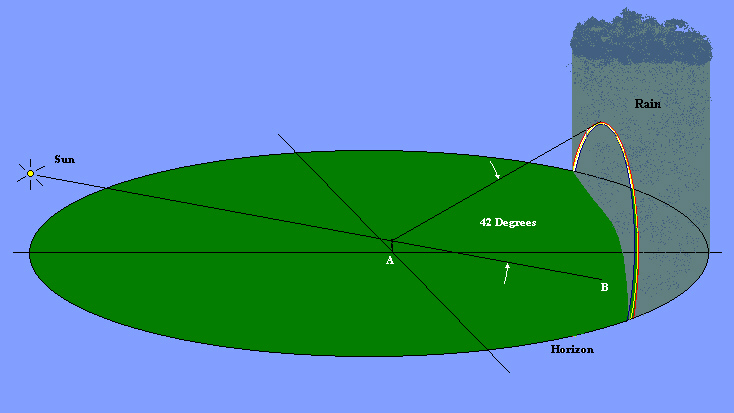

Rainbows have captured people’s imagination throughout history. Because of the association of rainbows with thunderstorms, the Cherokee believed rainbows to be part of the colorful robe of the thunder god. In Norse mythology the rainbow was viewed as a bridge that connected this world with the realm of the Gods. To the Australian Aborigines it was the Rainbow Serpent, who worked to sculpt the world during the dreamtime. Iris was the goddess of rainbows in Greek mythology. From her name comes the word iridescence, the play of vivid changing colors. The afternoon thunderstorms that often form on summer afternoons can create ideal viewing conditions for these natural wonders. Rainbows are caused by sunlight hitting raindrops and reflecting back to our eyes. Every wavelength of light takes a slightly different path through the raindrop. Each raindrop therefore acts like a tiny prism, spreading the sunlight into different colors. If you have enough raindrops of the right size, a rainbow is formed. To see a rainbow you must be looking directly away from the sun and toward an area of rain. In Figure 1 below, an observer is standing at point “A”, facing towards the right. The observer’s visible horizon is indicated by the green ellipse. If you draw a line from the sun though the eyes of the observer, it points towards “B”, the anti-solar point. Rainbows always form at an angle of 42 degrees from the line from the observer’s eyes to the anti-solar point. It follows that the lower the sun is to the horizon, the higher the rainbow rises into the sky.

Most rainbows are between 1 and 1-1/2 miles away from us, but they can be much closer. The next time you see a rainbow, be sure to follow the bow to the horizon. The rainbow that appears to be far away may pass in front of a ridge only a few hundred yards away. Since the rainbow always forms at an angle of 42 degrees from the anti-solar point, you cannot get closer to a rainbow by walking toward it. It will always appear the same size, seeming to recede from us as we try to approach. As Dr. E. C. Krupp says in his book, Beyond the Blue Horizon, “We generously inform people about the pot of gold at the end of a rainbow, knowing no one is likely to get there before we do.” Because each person looks from a slightly different direction, no two people see the same rainbow. In fact, if you create a rainbow very close to you with the spray of a water hose, you may see two overlapping rainbows, one created by each eye. This can be verified by closing one eye at a time. The colors in rainbows can vary with the size of the raindrops that form them. If the size of the water drop gets very small, a whitish “fogbow” is formed. At night, “moonbows” can be created in exactly the same way as rainbows. Because the moon is so much fainter than the sun, moonbows seldom show color. There are even dewbows, formed by sunlight reflecting from drops of dew on a smooth grass surface. If conditions are just right, a fainter secondary rainbow may form above the first rainbow at an angle of 51 degrees from line A-B. One such double rainbow is shown below. We photographed it in northern Australia, south of the town of Darwin. This secondary rainbow is caused by sunlight reflecting twice within each raindrop. The sky is often darker between the primary and secondary rainbows than it is elsewhere. This darker zone is called Alexander’s dark belt.

The colors in the primary bow typically fall in a certain order, starting with the longest wavelengths of light (red) on the outside of the primary bow and going to shorter wavelengths (violet) on the inside of the bow. This is where Mr. Biv comes in. Many schoolchildren were taught the memory device of Roy G Biv, where the letters of the name denote the sequence of colors in the primary rainbow: Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo and Violet. Of course we’re really looking at a continuous spectrum of color from red to violet. But it helps to remember the order of color change. If you look closely at the colors in the secondary rainbow, you’ll see that the colors are reversed from the primary rainbow. This reversal is caused by the extra reflection within the raindrops that form the secondary rainbow. Vib G Yor?

There are other neat things to look for in rainbows. In bright rainbows, you may see several “supernumerary” bows on the inside of the primary rainbow. These bows alternate between pink and green. According to M.G.J. Minnaert in Light and Color in the Outdoors, a setting sun, because the atmosphere has scattered its shorter wavelengths of light, can create an all red rainbow. It is also said that that you can sometimes see a rainbow shimmer when it thunders. This effect is apparently caused by thunder-induced vibration causing a temporary change in the size of water droplets composing the cloud. If you are looking at a rainbow’s reflection in a still lake or other body of water, you may see yet another fainter rainbow in the sky above that is not the secondary rainbow. This additional rainbow is caused by the reflection of the sun’s image from the surface of the water. The fainter rainbow fits exactly with the reflection of the primary rainbow to make a complete circle. And finally, can birds, as Dorothy sang, fly over the rainbow? Complete circular rainbows have been seen by pilots flying over clouds. These are not to be confused with the much smaller “glory” that can sometimes be seen encircling the shadow of an airplane on the clouds below. Birds, at least the high flying ones, could fly over a circular rainbow, providing they were flying above a layer of clouds. If not “happy little bluebirds”, then perhaps contented cranes or giddy geese. Delighted ducks? Whether birds fly over rainbows or not, many of them can experience the same dazzling colors that we do. Few sights are more beautiful than a bright rainbow against the dark backdrop of a summer thunderstorm. Rainbows lift our spirits, reminding us that no storm lasts forever, that the sun will again shine. Somewhere beyond our calculations, somewhere over Roy G Biv, rainbows continue to inspire us.

|